Giardiasis

The symptoms and causes of many infectious diseases are often straightforward. Description of the disease comes first. Some diseases share symptoms and must be differentiated. Then there is the identification and characterization of the infectious agent. Sometimes it isn’t too difficult to find and identify the culprit. If we look at typhoid fever, the first step was to distinguish it as a unique disease, then isolate and identify the typhoid bacillus. Most other diseases are the same: define the disease, describe the pathogen. But with some diseases, the organism is elusive and evades detection, and many years of searching are needed to find the organism responsible.

In the case of one common disease, the straightforward approach didn’t work too well. The organism we call Giardia has been known to exist for a very long time. Reportedly, Antonie van Leuwenhoek, the first to visualize tiny creatures with a microscope, described it in his own stool specimen. That was in the 1660s, over 350 years ago. The organism, a single-celled animal that’s easy to see with a good microscope, was fully described in the late 1800s. But its role in disease, now indisputably accepted, was debated for nearly a century.

Part of the confusion over Giardia’s role in disease is due to the organism's variability and different immune responses in those infected with the organism. When we get typhoid bacillus, we’re sick. Some can carry it without symptoms, but, for the most part, there is no doubt about the illness. With Giardia, though, illness doesn’t always follow infection. Many harbor the organism in their intestines with no symptoms whatsoever. Some are only mildly ill. Some get very sick indeed. With intestinal disorders in general, the cause is often elusive. Many cases of acute diarrhea, presumably caused by a microbe, go undiagnosed. Just tough it out, and the ailment is likely to go away. So seeing Giardia trophozoites or cysts in a stool specimen for many years raised the question: is it the Giardia causing the ailment, or is it some other non-identifiable cause? The subject was hotly debated. Even the creature's name has been disputed, with some preferring the species name lamblia, others duodenales, and others intestinalis. That discussion still goes on.

Today, the role of the little flagellate we call Giardia as a cause of an intestinal disturbance is no longer a matter of debate. The parasite can be carried within a person with no or few symptoms. But sometimes, the disease it causes can be quite serious. Malabsorption, diarrhea, weight loss, lethargy. Those are the main symptoms of those afflicted in more developed countries. Giardiasis can be devastating when combined with other conditions, such as parasite infestation and poor nutrition, which is often the case in less developed countries.

The genus name comes from a French zoologist, Alfred Mathieu Giard. The species name lamblia is derived from the Czech scientist who first described it in scientific literature. It seems appropriate that the parasite's name has undergone numerous changes through the years because its discoverer also underwent several name changes. Wilhelm Lambl spoke and published in several languages, including German, Czech, Russian, Polish, Italian, and French. He would often publish with a spelling of his name suitable to the language used. A very learned man, Dr. Lambl traveled and researched thoroughly around the countries of eastern Europe, and he became the chief pathologist at several prestigious hospitals. He first described Giardia from the stool of a 5-year-old child in 1859, naming it Cercomonas intestinalis. Dr. Giard later added a great deal to knowledge of the parasite’s life cycle. The proposed name of the organism was bandied about for several years, and many variations emerged, but it was eventually changed to honor its two discoverers,Giardia lamblia. Today there are two synonymous species names, duodenales and intestinalis, but it’s the same organism.

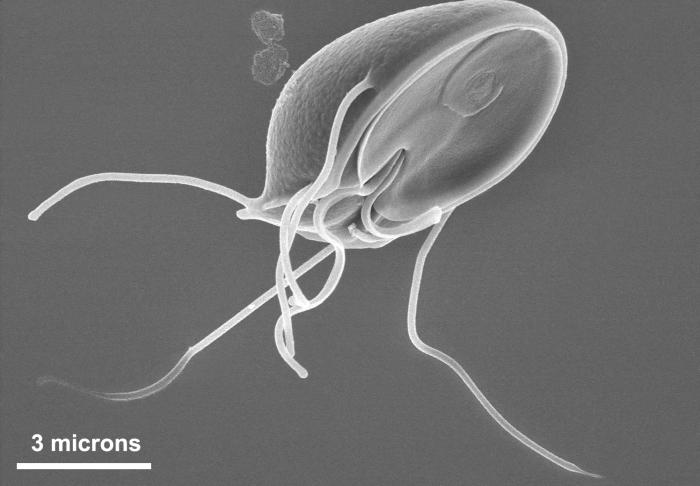

Giardia exists in the external environment as an oblong cyst. When the organism leaves the body, it does so in the cyst form to make it resistant to the harsh external environment. The cysts are remarkably resilient. They can last in still water for several months, provided the temperature doesn’t rise too much. We get sick from Giardia by drinking water containing cysts, and it doesn’t take much. Just a few dozen cysts will be enough to infect. Once the organism goes through the stomach acid, the cyst wall is ripped away, and the parasite emerges. It is a one-cell creature, but it has a lot of organelles. For one, it has four pairs of flagella, eight in all, to help it scoot around. It has a distinct type of motility, resembling a “falling leaf.” It has not just one but two nuclei. Perhaps the parasite's most significant asset is a large, conspicuous disk on its bottom, or ventral, side. It looks like a suction cup, the kind of thing you press on to get a hook to stick to a window. Whether there is any suction involved is unknown, but it is with the ventral disk that the creature attaches to the wall of the upper small intestine, either the duodenum or the jejunum. It hooks onto the lining of the intestine, and it won’t let go. Once established, it starts to feed, then reproduce.

Giardia feeds at the expense of the intestinal lining, causing damage. The organism produces two sets of enzymes to steal nutrients from the host cells. The first are proteases that break down the host cells' mucin lining. These proteases damage the host cell surface, allowing nutrients to flow out for the parasite’s nourishment. The second set of proteins it produces are called tenascins. Our cells have various types of these to manage the adherence of one cell to another. Some help the epithelial cells stick together; others drive them apart. Giardia manufactures the kind that leads to the lack of stickiness between cells, further releasing nutrients to engulf.

This release of nutrients from the host cells needn’t be too traumatic. If everything goes well, the parasite and the host can get along without much damage. In such cases, the symptoms of the disease usually aren’t too bad, or aren’t noticed at all. But with all these nutrients flowing out of damaged cells, it creates an opening for other organisms in the area, namely bacteria. Just which bacteria have access to it depends on which bacteria are present in the individual’s gut microbiome. Some bacteria are by their nature inflammatory, others much more benign. A good part of the progression of the disease depends on which bacteria are present and how aggressive they are.

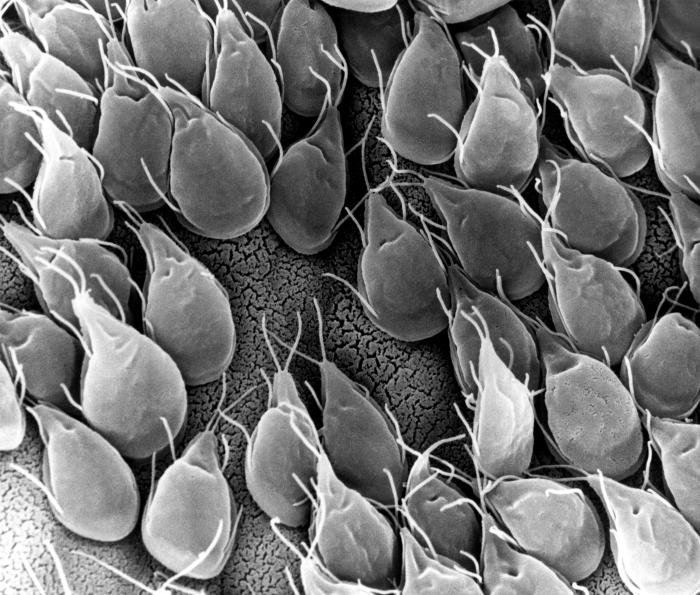

Another factor in the disease progression is the number of parasites covering the intestinal wall. Giardia is such a good progenitor that the upper intestine is crammed with masses of the little devils in a short time. They adhere to the intestinal wall's cells, forming a film. This mass of parasites can interfere with the physiology of the intestinal wall, blocking the absorption of nutrients and altering the normal functioning of the area.

All this activity obviously will catch the attention of the immune system. One of the chief defensive measures against an organism like Giardia is the release of secretory antibodies, IgA, into the area. When coated with antibodies the parasites cannot function properly, and their elimination is imminent. To overcome this, Giardia has devised an ingenious scheme. It changes its surface antigens. When an antibody to one surface protein is formed and begins to attach, the organism develops another one not recognized by the antibody. A different antibody must be created, buying the parasite more time. Giardia can make many other surface proteins, so the game goes on with the result of the organism establishing a long-lasting infestation.

The organisms receive some signal, possibly the attachment of antibodies, which induces them to begin turning into cysts. The cysts have a hard shell covering, allowing them to pass through the intestinal tract and into the environment. They can persist for quite a long time, especially in cooler temperatures. It only takes a few dozen cysts to set up an infection in a new host.

There are many different species and strains of Giardia and many different hosts that can be infected. Fortunately, the strains that infect domestic animals, such as dogs, do not infect humans. For some reason, those that infect beavers do, so that is one reason it’s not a good idea to drink mountain stream water. Beavers (or other humans) may have pooped in the water upstream, and the cysts are viable. One nickname for the disease is “beaver fever.”

The organism of Giardia was discovered in the late 1800s, but it wasn’t until 1981 that the World Health Organization recognized it as a pathogen of humans. Finding the organism in a stool specimen does not mean the person is sick. There are so many variables, such as the host's immune status, the strain of infecting organism, and the strains of extraneous bacteria that may cause a secondary infection, that the disease progress cannot be predicted. For those who do become ill, the symptoms are variable. Some have mild discomfort, perhaps bloating, belching, flatulence, mild diarrhea, or constipation. Some become quite ill, with severe cramping, marked diarrhea, and weight loss. Weight loss is connected to the malabsorption of nutrients, especially fats and vitamins. Loss of appetite also factors in. The disease can proceed for several months, and a twenty-pound weight loss is not unheard of. The condition needn't be life-threatening for those previously healthy with access to good nutrition. But the effects of a Giardia infection can be devastating for those in impoverished countries who don’t have access to good nutrition and have other parasitic diseases. In children, it sometimes means stunted growth and physical and mental abnormalities.

The diagnosis of giardiasis is made by laboratory testing. Several tests are available. The tests detect the organism in a stool specimen. Since the cysts are passed intermittently, it’s necessary to collect multiple specimens over several days.

Standard treatment for giardiasis in developed countries has traditionally been the anti-microbic metronidazole, commonly called by its original trade name Flagyl. (Flagyl and alcohol don’t get along well together; a patient taking Flagyl should avoid alcohol). There are other related drugs (nitroimidazoles) that can also be used. Usually, just a few days of treatment and you’re as good as new.

Giardia trophozoite showing ventral disc; Numerous Giardia showing attachment to intestinal microvilli. (PHIL)